ACTION AREA 2: Early Detection by HPV Testing

Late diagnosis of cancer increases the risk of serious disease and death. Cervical cancer screening can reduce cervical cancer mortality by up to about 90%, according to a study of its impact in Europe.54 Screening programmes will remain an essential element of the management of cervical cancer for the foreseeable future. This is because vaccination only began in Europe in 2008 and there are no countries that have achieved 100% vaccination uptake. Moreover, vaccination does not protect from all the oncogenic HPV types and some cases of cervical cancer are not caused by HPV. Many millions of women therefore remain at risk of HPV infection and cervical cancer. As the vaccinated cohort expands, however, screening will become a more straightforward process for women and clinicians.

Currently there are no screening programmes available for any of the other HPV-caused cancers, including those affecting men. Currently-available screening tests for oropharyngeal cancer are insufficiently accurate and the benefits and potential harms (such as overdiagnosis or unnecessary treatment of patients with false-positive results) are unknown.55 Screening for anal pre-cancers is technically possible and has been suggested for high-risk groups, such as men who have sex with men, people with HIV/AIDS, and women with a history of HPV-caused cervical, vaginal or vulval cancers. However, the evidence of benefit has not yet been clearly established.56

More research is needed into potential screening programmes for the non-cervical HPV-caused cancers; in the meantime, the best way of achieving early diagnosis is through public education about the symptoms and training the medical workforce, including dentists, to detect the early signs of all cancers. It has been suggested that dentists and dental hygienists may have a potentially important role in the opportunistic detection of oral lesions 57,58 but robust evidence for this approach is currently lacking, particularly in the case of oropharyngeal cancer.

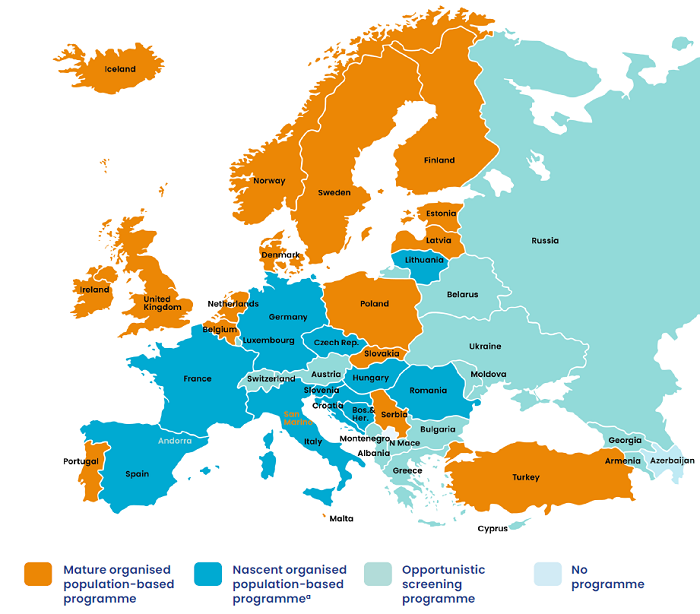

A recent analysis of cervical cancer screening across 46 European countries found that, with the exception of one country (Azerbaijan), all had a screening programme of some sort.59 17 had population-based organised programmes described as ‘mature’ and 11 had ‘nascent’ organised population-based programmes. Organised population-based screening refers to an approach in which invitations to screening are systematically issued by public authorities to a defined target population, within the framework of a documented public policy specifying key modalities for screening examinations. This approach is recommended in the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening.60

Another 16 countries had opportunistic programmes, meaning that their success depends on the initiative of individual women and their doctors. This approach to screening often results in high coverage only in certain parts of the population, while other groups, usually with a lower socioeconomic status, have more limited uptake. Opportunistic programmes result in not only uneven coverage but also less consistent quality assurance, limited impact, and reduced cost-effectiveness.61

Also, while cervical cancer screening and cancer treatment is free of charge in most Eastern European and central Asian countries in the WHO European region, few cover the cost of following up a positive screening test or the treatment of precancerous lesions.62 The value of free cervical cancer screening at no cost is limited unless the treatment of precancerous disease is also provided free of charge.

Uptake of screening is highly variable between and within countries. Rates vary from over 70% in some EU member states to around 30% in others.64 The highest recorded rate is in Sweden (83% in 2017) and the lowest in Romania (1%). In countries with historically high screening rates, uptake has been falling in recent years. Overall, in 2014, about 14% of EU women aged 20-60 had never had a Pap smear test. In every country, women with lower educational attainment are least likely to have been screened.

Figure 2. Countries in the WHO European region with cervical cancer screening programmes63

a Some of the country programmes in this group are reaching significant screening coverage rates and cervical

cancer reduction trends.

HPV testing is the most effective, and accurate, method of cervical cancer screening. It is supported by the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening65 and is now being adopted by an increasing number of countries in place of cytology-based screening. However, it is not yet universal. Finland, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain and Sweden, as well as Norway, Turkey and the United Kingdom outside of the EU, have either started to implement HPV testing on a regional or national level or plan to do so. It has also been piloted in several other countries, including Poland and Portugal.66

As part of the process of introducing HPV testing, women need to be fully informed about the nature of the test (for example, they need to know that being HPV positive is not on its own evidence of a pre-cancerous lesion) and to understand the nature of HPV infection in order to avoid potential relationship difficulties and stigma. In the absence of this understanding, some may believe they have acquired the virus from an unfaithful partner or their partner may assume that she has become HPV+ as the result of sexual activity outside of their relationship. There is also a need for clinical consensus about how best to follow-up positive tests.

HPV testing does not have to be clinic-based. HPV self-sampling is now an option. Women use a kit, either provided at a clinic, sent to their homes or delivered there by a health worker. Greater use of this tool could undoubtedly help to improve access to screening programmes and improve uptake.67 It may be particularly suitable for women who are unable to access standard screening facilities, perhaps because they live in countries with less provision or in remote areas or have a disability, or where there are cultural barriers or previous traumatic experiences. It is essential, however, that self-sampling programmes address the potential risks of lower rates of follow-up by patients or increased patient anxiety following a positive result.68

Self-sampling has already been incorporated into the cervical cancer screening in the Netherlands and in the Capital Region of Denmark69 and should be considered for wider roll-out across Europe. Self-sampling could also help mitigate the disruption caused to cervical cancer screening programmes by COVID-19 although it is essential that ‘mainstream’ screening resumes, where it is safe to do so, as soon as possible following the guidance developed by EFC and ESGO.70

CASE-STUDY

HPV Testing in Turkey

A cytology-based cervical cancer screening programme was introduced in Turkey in 2004 but only reached 3% of the target population by 2012. Key barriers included a lack of coloscopists and cytopathologists and poor quality assurance for the testing process.

HPV testing was introduced in 2014 in an attempt to increase screening uptake, to provide a more accurate test, and to eliminate the human resource bottleneck. Women aged 30-60 were now invited for screening every five years, a well-defined protocol for screening intervals and referrals was introduced, and a single nationwide centralised diagnostic laboratory was established. The testing service was delivered by family physicians and nurses.

Two samples are taken from each woman which enables cytology testing for those found to be HPV-positive without women having to return for a separate test to provide an additional sample. Because only HPV-positive tests have to proceed to cytology, larger numbers of women can be screened without an excessive burden being placed on the coloscopy and cytopathology workforce.

HPV testing enabled a ten-fold increase in screening coverage to be achieved by 2017, by that time reaching 35% of the target population. The uptake among 30-45 year olds specifically reached 64%. The success of the programme suggests that HPV testing could be a feasible option for other upper-middle-income and socially conservative states in the European region.

-Guletkin M, Karaca MZ, Kucukyildiz I, et al.71

CASE-STUDY

HPV Self-Sampling

Women who are underscreened for cervical cancer are more likely to participate when offered HPV self-sampling kits, according to a trial in Belgium.

The women, aged 25-64, were recruited from attendees at a GP practice in a Flemish municipality near Brussels who had not be screened for cervical cancer for at least three years. The GPs invited 50% of the women to use a a self-sampling kit. This could be used at home and then sent by post to a laboratory or returned to the GP practice. The other 50% of the women were asked to make an appointment for a Pap smear test at the practice or with a gynaecologist.

78% of the self-samplers completed the test compared to 51% of those offered a Pap test. Women in the self-sampling group were 1.5 times more likely to participate in testing. The trial suggests that direct GP involvement leads to higher rates of self-sampling than other systems, such as sending kits to women by post. Other studies have also shown that the involvement of community health workers can lead to an increased uptake of self-sampling.

-Peeters E, Cornet K, Devroey et al.72