5. Shared Decision-Making

You have a right to:

Participate in Shared Decision-Making with your healthcare team about all aspects of your treatment and care.

Three key questions that every cancer patient may choose to ask:

- May I discuss the approach that we will take in making decisions about my care and agree how my voice is heard?

- May we share decision-making so I feel empowered to decide on my care options?

- Does our cancer service encourage patient engagement, involvement and empowerment?

Explanation

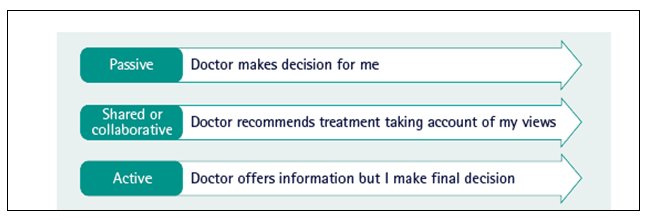

European cancer patients should have a choice as to how decisions are taken about their cancer care and that choice should include Shared Decision-Making (SDM). Patients will have individual views about what is important in their life at the time of diagnosis and how they wish decisions to be made. While some patients may prefer for the doctor to take the decisions; most will prefer to take the decisions themselves. However, increasingly in good modern clinical cancer practice, a shared or collaborative approach is being employed, in which a doctor recommends treatment but takes account of the patient’s situation and views after careful discussion.

SDM allows patients to fully inform themselves before making any choices about their treatment. Patients should have the possibility (either through the hospital or a patient advocacy organisation) to discuss with other patients who have gone through the same treatment successfully, to better understand the consequences of the treatment and how it will affect their quality-of-life. SDM also entails understanding the context in which the patient lives and identifying variations in the treatment plan, based on the patient’s specific situation. A fully informed patient can also have the option to not (or to no longer) receive specific anti-cancer treatment such as surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

SDM requires good communications between the patient, the patient’s carers and family and the healthcare cancer professionals. The approach has to be tailored carefully to fit the needs and preferences of individual patients, whose views for the level of input into decisions will vary. The family/social/cultural situation may also impact on the individual patient’s care and should be considered. There is no single “best approach”. Communicating choices about treatment must begin by clarifying the patient’s knowledge about cancer and its treatment and how much involvement in decision-making the patient wants, both at diagnosis and throughout their journey. It is also helpful to clarify what the patient considers to be a ‘good’ outcome from treatment. Family involvement is often helpful, although the views of family members may be different from the patient’s perspective.

There is good evidence that clinical decisions should be informed by a consultation between the healthcare professional and the patient that involves clarification of the patient’s wishes and preferences, clear information about the purpose of treatment and the benefits/risks of the treatment. Patients want a good doctor-patient relationship: a doctor who is approachable, understanding and provides respectful care. Information needs to be uncomplicated, specific, in lay language and as unambiguous as possible. Communication which strongly directs a patient to a single option can have negative consequences. Evidence suggests that appropriately-judged SDM will improve patient outcomes and wellbeing and reduce the risk that patients will subsequently regret the decisions that have been taken.

SDM is a key component of patient involvement and engagement, in which healthcare professionals encourage patients to influence how their own care and healthcare services are delivered. This relates to the wider concept of patient empowerment, in which patients may undertake self-driven initiatives to influence how healthcare services can be improved.

Supporting Literature and Evidence

Decision-making preferences are characterized in Figure 17 (59), although unwell and anxious patients may find it difficult to decide their treatment preferences. Shared decision-making can be challenging, especially if a clinician or MDT have a strong view. A treatment preference may be right for the average patient but not right for an individual. Shared decision-making should result in less regret about the decisions taken, aid coping, resulting in better treatment compliance which should improve QoL and survival.

Figure 17 Decision-making preferences (59)

Cancer, which has never been easy to explain, is now becoming even more complex as its genetics, pathology, diagnostic tests and treatment become more precise and detailed. Describing risks and benefits is challenging (137). Cancer professionals require training and experience in communication to elicit truly educated/informed consent (59,113).

In a large US study (138), if patients showed strong evidence of self-efficacy (see above for definition), high levels of shared control were sought. The highest rates of patient control were seen in chemotherapy decisions; the highest rates of physician control were seen in surgery and radiation decisions. Ring et al (139) found in women over 70 years with breast cancer that 58.5% preferred shared decision-making. Men with prostate cancer are faced with challenging initial decisions that can include options for therapy with radical surgery, substantial radiotherapy treatment, or a policy of active surveillance without initially the introduction of major treatment. Wilding et al (140) surveyed 17,193 men after prostate cancer treatment and found that regret about the treatment decisions taken was more common when they reported that their views had not been taken into account.

In delivering patient-centred care and improving communication with patients, healthcare professionals have a powerful influence on decision-making; however, they are no longer the patient’s only source of information. Decisions may involve other opinions, including those found on the internet and social media. Decision aid tools providing clear, comprehensible information in an appropriate format will help shared decision-making (59). Clear and concise communication is key to high-quality, patient-centred care (59). All patients faced with these and other challenges, will receive information from clinicians and the multidisciplinary clinical team but also information will come in from families, friends, and other patients and in modern practice increasingly, internet sources.

Explaining the risks and options to a cancer patient, especially in complex modern practice, is inevitably challenging (59, 137). Not only patients but also many healthcare professionals will be operating at the limit of their statistical knowledge and may be helped by useful decision aids (137). For example, the decisions faced by breast cancer patients at the time of diagnosis when they are contemplating the onset of their treatment can be especially challenging. There may be difficult options including different degrees of surgery and different modalities of adjuvant therapy (141). Patients will of course be very concerned to know their probability of survival, but also, they will be concerned to avoid toxicity and inconvenience from their treatment and to identify the most acceptable outcome for them in terms of appearance and body image. An example of a decision aid tool is the PREDICT-UK online tool which helps patients and clinicians see how different treatments for early breast cancer might improve survival after surgery. This facilitates the discussion and shared decision-making about adjuvant treatments following surgery. It has been recently recommended by the NHS (142).

A Cochrane Systematic Review was applied to studies which had sought to clarify the impact on patients of the treatment and screening options which were presented to them. The Review considered 55 clinical trials across the wide range of treatment and screening options. Its conclusion was that where patients had a greater participation in decision making, where their knowledge was greater and they had more accurate perceptions, then they had greater comfort/satisfaction with the decisions taken (143).