Introduction

This paper is a supporting paper to the European Code of Cancer Practice (The Code) (1), and summarises the medical literature and evidence upon which The Code is founded. The Code is a patient-centred initiative which identifies 10 key patient Rights that underpin the delivery of good clinical cancer practice and which, if implemented for all European citizens, would improve patient survival and quality of life (QoL). The Code is built on the European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights, which was launched in the European Parliament in 2014 (2-3) and updated in 2016 (4).

In order for the reader to have a ready insight into the relationship between each Right within The Code and the supporting literature and evidence, in this Medical Literature and Evidence Paper (MLEP) we have included the components of The Code. The introductory sections of the MLEP cover the scale of the challenge we face to improve the outcomes for Europe’s cancer patients, the vision of what may be achieved, and the wider context of cancer control which considers relevant epidemiology and the important roles for cancer prevention and early diagnosis. The meaning of good practice in clinical cancer care is described and the vital role of the partnership between patients, patient advocates and cancer professionals is emphasised. The essential contribution of patient involvement, patient engagement and patient empowerment is explained. The importance and future contributions of Research and Innovation are summarised. Each of the 10 Rights of The Code are then presented in the form in which they appear in The Code and for each a discussion of the supporting literature and evidence follows summarising key references and websites. It is intended that the MLEP may be read as a whole, or that the sections on each Right may be read separately.

The Code itself is written to be used by patients who have been diagnosed with cancer and may be useful at any part of the patients’ journey. However, it may also be useful to indicate the core patient- centred aspects of cancer care to a wider audience including cancer professionals. The MLEP while it is written to support The Code, it may be used by a wide audience including patients, patient advocates, cancer professionals and trainees and a glossary of terms will be provided.

The Challenges and Disparities that European Cancer Patients and Health Systems Face

Our rapidly increasing knowledge of the biology of cancer and its detection and treatment has resulted in radical improvements in recent decades in outcomes for many patients with cancer, allied to an enhanced patient experience and better QoL (4). Over half of all patients with cancer who receive state-of-the-art diagnosis and treatment can expect long-term survival beyond 10 years after their diagnosis, and for most of these people, the outcome is a cure of their disease. Good QoL is now achievable for many patients on active therapy and for long-term survivors (2-16). Despite these advances, cancer and the provision of cancer care still places a significant burden on Europe’s patients, citizens and economies (6). As the European population ages and if lifestyle-associated cancer risks such as smoking and obesity are not adequately addressed, then in many European countries more than half of the population will develop a cancer at some time during their lives.

Modern healthcare is facing massive challenges. The increasing complexity of diagnostic approaches and treatments; the spiraling costs of healthcare; the ageing population and the recognition of the need for patients to be well informed and well supported are all creating significant pressures and promoting health inequalities (1-17). For certain cancers, notably brain tumours, oesophageal, pancreatic and lung cancers, progress remains limited and prognoses are generally poor. It is crucial to redouble our research efforts into the causes of and treatments for these hard-to-survive cancers (18-19).

A number of current research strategies are beginning to make an impact on treatment and care, on cancer outcomes and they address the challenges outlined above (14, 18-20). Precision oncology (20-21) makes better use of well-validated biomarkers and imaging approaches to guide diagnosis, prognosis and treatment choice. New and increasingly effective treatment modalities such as immunotherapy are helping to improve outcomes (14, 18-20, 22). New technologies in radiation (23, 24) and surgical oncology (25-26) allow better targeted and less invasive treatment approaches, decreasing treatment burden and improving long-term QoL along with tumor control. Health informatics enhances the collection, curation and deployment of patient data and data analytics at scale and machine learning approaches have the potential to solve many healthcare problems (14). Technologies for rapid, point-of-care diagnostic procedures and imaging are improving detection and early diagnosis. Patient support strategies and patient advocacy organisations are becoming commoner, more robust and more effective (7). However, there remains a real danger that healthcare in future will become a confusing and unsatisfactory experience for patients and that cost constraints will make it difficult to provide the numbers of skilled health professionals required to help patients navigate their way through such a challenging environment.

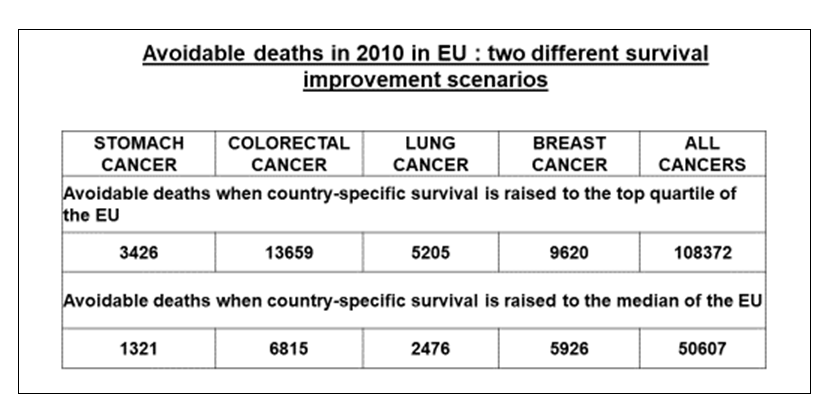

Europe provides some of the best cancer care in the world and conducts high-quality, globally recognised cancer research. However, there are still significant disparities between European nations and regions in a number of key areas including: accessing cancer care; information for citizens or patients about cancer care; delivering optimal treatment and outcomes; access to the full range of expertise of multidisciplinary cancer care teams; good communications and appropriate shared decision-making; integrating cancer research and innovation; ensuring the best QoL for patients on treatment and thereafter; integration and access to supportive and palliative care and supporting cancer survivors (1, 2, 5, 7, 8). Overall, there are major disparities in the quality of cancer management and in the degree of expenditure on cancer control across European nations (2-17, 27, 28). This results in unacceptable inequalities in cancer outcomes for European patients (28). Table 1 shows the results of a research study in which the impact on patient survival of implementing existing good practices in cancer care were modelled.

Table 1. The top panel shows the impact on cancer survival in the EU of raising the outcomes of all cancer patients to match those that are already achieved in the top 25% of countries, which are making use of most of the known good cancer practices. In the lower panel, the impact is shown of raising the survival of all European patients up to the median average for EU countries - perhaps a more readily achievable goal. The study indicated that 50-100,000 additional people each year could survive their cancer diagnosis, if good practices were comprehensively implemented across EU countries (28).

Importantly, improvements in quality of care, translation of research discoveries into clinical benefit and promotion of innovation will have to be achieved within affordable and more efficient healthcare models (2-16).

Prevention and Early Diagnosis

The Code is a patient-focussed initiative and therefore mainly addresses good practice in diagnosis, treatment and care. However, it is important to emphasise the key roles that cancer prevention and early diagnosis including screening, play in enhancing cancer control and in the reduction of cancer morbidity and mortality. These areas are already addressed in the European Code against Cancer (ECAC, 29). The components of good practice in cancer prevention and early diagnosis include:

- Effective prevention (lifestyle, vaccination, public health, etc, (29))

- Well-managed screening programmes (cervix, breast, colorectal cancer [CRC] (29)

- Prompt diagnosis and rapid referral in primary care, with timely access to best care for patients at all ages including any socially disadvantaged groups (4, 5, 11, 29-31)

The 70:35 Vision

In countries with the best diagnostic and clinical practice and excellent organisation of their cancer care, long-term cancer survival is experienced by 60% of patients. There is now substantial guidance on improving cancer outcomes at national and European levels and evidence that this guidance can improve healthcare and enhance cancer practice. A significant number of improvements have been mediated through the implementation of robust national cancer control plans. However, concerted and consistent action is needed to bring all of Europe’s cancer care up to an acceptable and equitable level and this will involve informing and empowering patients, providing adequate staff, facilities, equipment, material including medications, information systems, and the development and training of a wide range of cancer professionals (4, 5, 11).

After wide consultation, a goal of the work required to improve cancer outcomes was agreed. Our aim is to reach 70% survival on average beyond 10 years for all European citizens by 2035, improving both the length and quality of cancer patients’ survival (4).

This “70:35 Vision” will be addressed by two processes simultaneously:

- Sharing and implementing good practice in cancer diagnosis and care. An actively managed, systematic approach to identifying and sharing good practice in cancer control and the best available cancer care across European countries and regions is needed. We envisage that this process by itself would raise long term patient survival from an average of about 50% to around 60%, which is already being achieved in certain European countries.

- More intense research and innovation in discovery, translational, clinical and health-related cancer sciences. If at the same time as sharing and establishing good clinical cancer practice, we also sustain and increase the intensity of research and innovation and the rapid translation of cancer research into clinical practice, there is the real potential for a further increment in long-term survival towards 70% and improvement in both quality of life and the patient experience. This may be based on ongoing research, largely informed by existing concepts and technologies.

This high-level goal of the 70:35 Vision will help to focus discussions and serve to communicate the scale of ambition to improve cancer outcomes.

Against this background, patient engagement and patient empowerment can become part of the solution to the delivery of acceptable, humane, patient-centred and technologically-robust care. If this is to be the case, then we have to craft approaches to allow patients to navigate and make the best of their healthcare system, promoting excellence and a patient-centred approach. Those tools have to have credibility for healthcare professionals. With this in mind, the European Cancer Organisation is developing a toolbox of materials that will help cancer professionals and cancer patients to work together to improve their communications and enhance the quality of care that can be delivered.

The European Code of Cancer Practice (The Code) is such a tool. It seeks to provide evidence-based information for patients in a readily accessible form, assist patients in navigating cancer care and generate a genuine and effective partnership with cancer professionals, which will ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Back to Medical Literature and Evidence for the European Code of Cancer Practice