7. Quality-of-Life (QoL)

You have a right to:

Discuss with your healthcare team your priorities and preferences to achieve the best possible quality-of-life.

Three key questions that every cancer patient may choose to ask:

- During and after my treatment, how will I be able to maintain the optimum quality-of-life so that I can live as normally as possible?

- Does our cancer service measure the quality-of-life of patients in any way, such as using Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs)?

- Does our cancer service actively consider whether people have emotional, social or financial problems pertaining to their diagnosis or treatment?

Explanation

European cancer patients should to live as normally as possible with the optimum quality-of-life following their diagnosis, during treatment and through survivorship. Patients must be thoroughly informed on both medical and non-medical aspects of care and survivorship. Patients and their healthcare professionals must work together to preserve quality-of-life, while maximising chances of survival or cure. This will mean a focus not only on the patient’s survival, their physical symptoms, test findings, the technological aspects of their care and the side-effects of treatment, but also the impact on daily functioning and wellbeing, relationship problems, work-related issues, financial hardship and social isolation. This may be particularly important and challenging when cancer treatments are associated with significant toxicity in the short, medium or long term. Striking the right balance in terms of survival and quality-of-life is particularly challenging where this risk of toxicity is associated with treatments that deliver only modest or uncertain improvements in the person’s survival. Maximising the quality of patient’s lives is now considered a hallmark of successful cancer care. Referring patients to patient advocacy groups will provide additional support, particularly on the issues that patients specifically find challenging.

Methods for measuring quality-of-life are now increasingly used in cancer care and clinical research, in particular Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs). PROMs are defined as ‘any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.’ PROMs provide a formal measurement of the patient’s experience of symptoms, treatment, daily functioning and health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL), and they reveal important patient-focussed information on quality of care. PROMs can be measured using carefully developed and validated questionnaires (sometimes called “tools” or “instruments”) in clinical practice and in clinical trials. PROMs are developed jointly by patients and professionals and include questions derived from patients’ concerns and experience.

Psychological distress is commonly experienced by cancer patients during their treatment and thereafter and is a major factor in poor quality-of-life, reflected in challenges such as self-esteem, changing roles of couples in relationships, social isolation etc. In a minority of patients, it may even precipitate a psychiatric disorder such as clinical depression. Healthcare services should provide psychological support, both to detect and manage such changes in the person’s wellbeing. During and after their treatment, many cancer patients may experience social difficulties in all domains of life in their homes, in their interaction with healthcare services, with personal finance, with family relationships and in housing and mobility. Cancer patients should expect that healthcare professionals and healthcare services are aware of these challenges and are able to advise on and mobilise the appropriate assessments and measurements, advice and support to reduce social and financial difficulties.

Supporting Literature and Evidence

The increasing emphasis on QoL comes from greater awareness of the needs of patients and also from an increasing ability to measure those needs using Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs). The first PROMs used in oncology were health-related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaires. These multidimensional questionnaires measure physical symptoms, psychological distress, the impact on daily functioning and patient perceptions of their QoL and well-being (153). In parallel, aspirations to provide better patient-centred care recommended PROMs for holistic needs assessment of all cancer patients, using screening tools such as the Distress Thermometer and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (154-155).

Traditionally PROMs, specifically HRQoL questionnaires, have been used in oncology trials as secondary outcome measures in addition to cancer outcomes such as overall or progression-free survival and this approach supported patient-centred clinical conclusions in a range of clinical trials. With the wider use of digital methods for data collection and electronic medical records, it has become feasible to collect PROMs in daily oncology practice and use them in real time to support individual patient care. PROMs data may be collected as a screening tool for symptoms or psychological distress, and also employed for monitoring symptoms and treatment response over time( 156-157). Feeding back PROMs data in a structured format to the clinician can promote patient-centred care by highlighting concerns and prompting discussions. A number of randomized clinical trials that studied the use of PROMs in the routine care of cancer patients during treatment showed that providing PROMs to oncology clinicians can help identify psychological and physical problems, facilitate patient–doctor communication, engage patients in decision making, and improve symptom control and patient well-being. Moreover, the use of PROMs to monitor symptoms during treatment and in subsequent follow-up did not only demonstrate improved HRQoL and patient satisfaction, but also improved symptom control and patient survival, along with a reduction in healthcare usage and costs thanks to more efficient use of resources, rendering it a cost-effective approach (158-162). Two systematic reviews of the 25 randomized controlled trials in this field have been conducted and concluded: ‘Despite the existence of significant gaps in the evidence base, there is growing evidence in support of routine PROM collection in enabling better and patient-centred care in cancer settings.’ (153, 163-164).

In order to move the field beyond clinical research and into routine patient care, international organisations such as the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) and the Quality of Life Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) have developed practical guidelines on how to incorporate PROMs in clinical practice (153). The Patient-Centred Outcome Research Institute of the USA NIH has published a “Users’ Guide to Integrating Patient-Reported Outcomes in Electronic Health Records” to facilitate integration of PROMs in the electronic health record, to enable the use of patient-reported data for clinical, research and administrative applications and thereby promote patient-centred care(165-166). Standardized reporting of the combined clinical and PROMs data will help clinicians and providers to evaluate treatment benefits from the patient perspective, collect information on late effects of treatments and potentially measure the benefit of rehabilitation interventions (153, 167). The SISAQOL project is an international consortium “Setting International Standards in Analyzing Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life Endpoints Data” aiming to improve the analysis and presentation of QoL data to patients and clinicians (168). Guidance on how to include the patient voice in the development and use of PROs and PROMs have also been provided (169).

Psychological distress and psychiatric disorder

‘Psychological distress’ includes worry, intrusive thoughts, low mood, poor concentration, sleep difficulties and appetite changes, below the threshold for a diagnosable psychiatric condition. In patients with cancer, the prevalence of mental disorder has been shown to be between 30% and 40% (170) commonly accounted for by adjustment, depression and anxiety disorders. Studies examining the prevalence of major depressive illness show figures varying from 8% to around 25% and the prevalence of anxiety disorder has been found to be about 25% (170). The prevalence rates of depression in adults with cancer are imprecise due to differences in study design; however, it is clear that psychological morbidity is a significant part of the cancer diagnosis for many people (170). It is suggested that all patients should be screened for psychological morbidity at key points in their disease, which include around the time of diagnosis, during treatment, as treatment ends, and at the time of disease recurrence if that should occur (170).

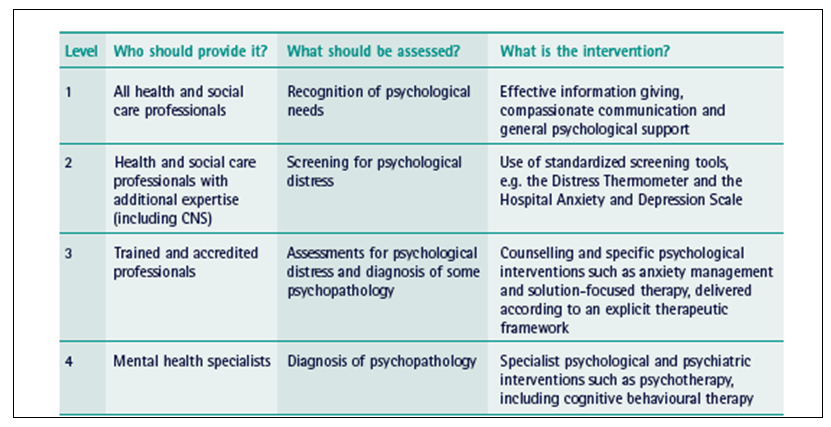

It has been recommended (171) that psychological support should be provided in a stepped care approach which addresses the needs of patients with few psychological needs through to those needing specific intervention (Table 10).

Table 10 (From 171). Recommended model of professional psychological assessment and support. CNS, Clinical Nurse Specialist

Oncology teams may not recognize psychological distress. Fallowfield et al (172) showed that 36.4% of screened patients had scores suggesting psychiatric morbidity, but less than one-third of these cases were picked up by routine care. For most patients presenting with psychological distress, recognition of their difficulties and addressing their concerns is the only intervention needed. Some patients may require more support than their oncology team can offer and specialists in mental health may be needed. In this regard, the International Psycho-Oncology Society (IPOS, 55) aims to foster training, encourage psychosocial principles and a humanistic approach in cancer care, and to stimulate research and develop training so that psychosocial care may be integrated with all clinical oncologic specialties for optimal patient care (55).

Social Difficulties of Cancer Patients

The social impact of cancer may be considerable, not only at the time of diagnosis, when immediate readjustments may have to be made, but also possibly over many years following diagnosis. Some cancer ‘survivors’ will be disease-free following their treatment, but others may attend hospital for monitoring, for multiple treatment cycles for chronic cancer or for palliative interventions. Early and late side effects of treatment are not uncommon, which may result in chronic disability and restrictions in performing daily activities. Patients at all stages of disease report problems in all domains of life (173-174):

- In the home (eg domestic chores, personal care, caring responsibilities)

- With services (eg support services, aids and adaptations)

- With finances (eg welfare benefits, mortgages/pensions), and regarding employment, including the self-employed

- Legally (eg sorting out family affairs, wills)

- With relationships (eg communication problems, new relationships)

- Concerning sexuality and body image, as well as recreationally (eg social and leisure activities,

holidays) - With housing and getting around

In addition to the direct impact of cancer and cancer treatment on everyday living, there are indirect ‘knock-on’ effects. For example, a patient may experience financial difficulties as a result of cancer and its treatment (eg loss of income or increased daily living costs), leading to detrimental impacts on family life, roles and relationships. A qualitative study found that patients and carers reported being unprepared for the financial impact following a cancer diagnosis, delaying taking action to address financial problems, which in some cases led to significant longterm problems such as debt or house repossession. Timmons et al (175) stated: ‘This study reveals the complex, multidimensional nature of the financial and economic burden cancer imposes on patients and the whole family unit. Changes in income after cancer exacerbate the effects of cancer-related out-of-pocket expenses. These findings have implications for healthcare professionals, service providers and policy makers.’

Although most patients are resilient and cope with the impact of cancer and its treatment on their lives, a significant minority struggle. In a population-based survey of more than 17,000 colorectal cancer patients (167), 15% of participants reported levels of social distress (measured using the 21-item Social Difficulties Inventory [SDI-21]) which if found in clinical practice would have warranted some form of further assessment or discussion with the clinical team (173, 174). Patients with multiple concerns or difficulties, including social problems, have been shown to be more likely to exhibit clinically significant anxiety or depression. Therefore, early detection is desirable and possible. For example, in Canada, the Distress Assessment and Response Tool (DART) programme provides an efficient and effective way of identifying those most at risk of poor social outcomes, leading to provision of appropriate advice, signposting for supportive self-management and referral to services for those most in need (173-175).